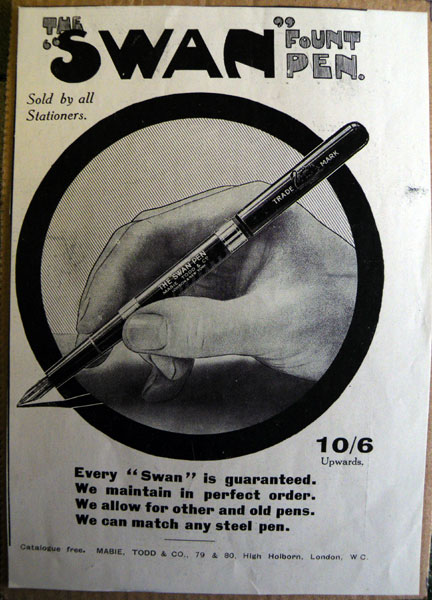

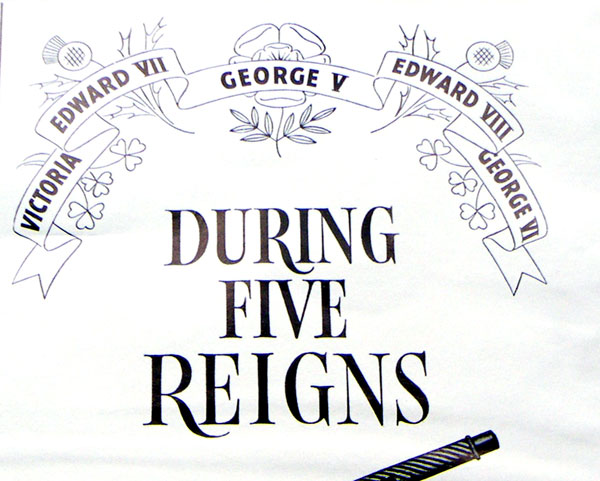

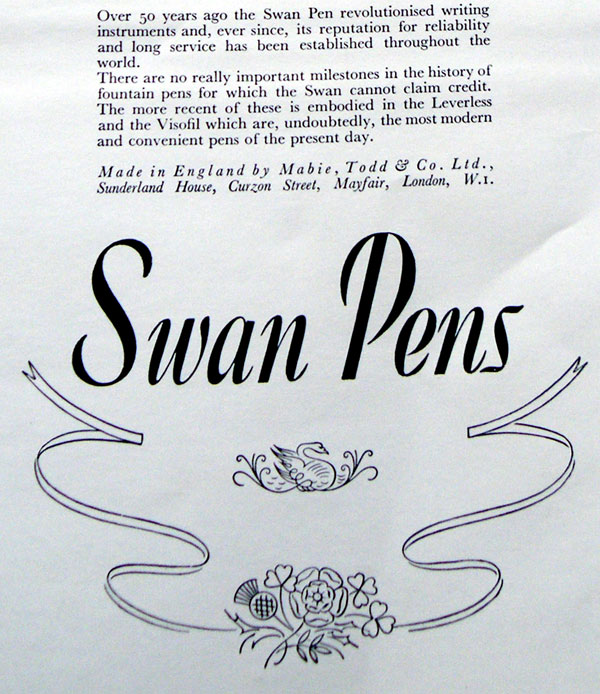

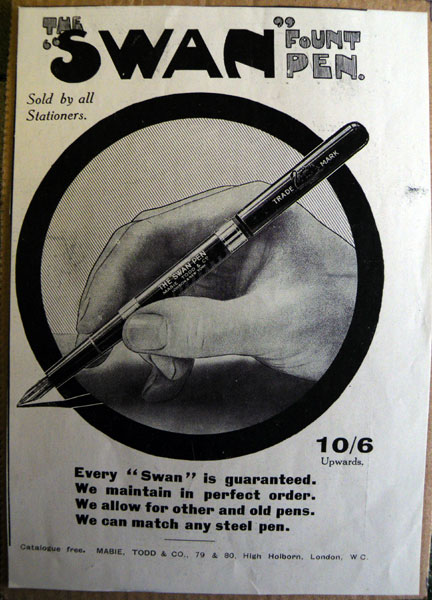

Mabie Todd, it must be said, always produced stylish adverts. This is true, in fact of most early fountain pen promotional imagery; the commercial artist is often undervalued but he or she is a true artist. The area of work within which he practices is irrelevant except to those who imagine that the value of art is expressed in those grotesque sums of money thrown around at Sothebys or Christies as the obscenely wealthy vie at the pig trough of self-aggrandisement.

The heading is in that strangely arresting, bulging text that Swan used for a few years. It’s followed by a little message in italic: Sold by all Stationers. That doesn’t need to stand out. This is 1913 and Swan is king! You would know where to get one. Then there’s the price – 10/6 – in very bold text with underneath, not so noticeable: Upwards. I think the message is to concentrate on the 10/6 and ignore the fact that the model illustrated, with its two barrel bands, will likely cost a lot more.

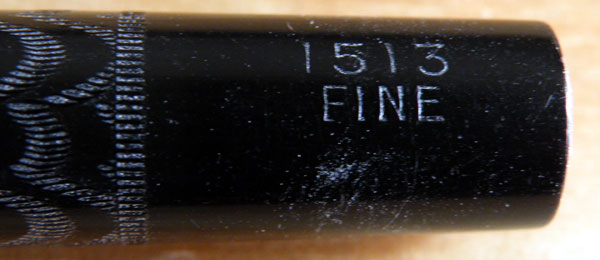

Then, in a bold sans serif font, is the company’s main message, reassuring and accommodating. The language is a little obscure to us now. You’ll be pleased to know it’s guaranteed and can be kept in good order. Like Waterman, Swan will fit any nib you want, including your own. To order, prospective purchasers sent a steel nib that replicated the gold nib that they wanted – fine, medium, broad, stub, oblique – whatever the customer desired, Swan could produce. And finally, in small print at the bottom, the address to write to for a free catalogue. Would that I could get that catalogue now!

The ring around the hand concentrates the eye wonderfully. The hand is behind the ring, the pen before it. Though impossible and a little Escher-like, this makes the pen the centre of your attention, and it is drawn in much greater detail than the sketchily-drawn hand. The pen breaks the “frame” of the circle in two places, and its shadow does so in a third. This play with the concept of space harks back to the Post-Impressionists’ borrowings from Japanese prints a generation earlier.

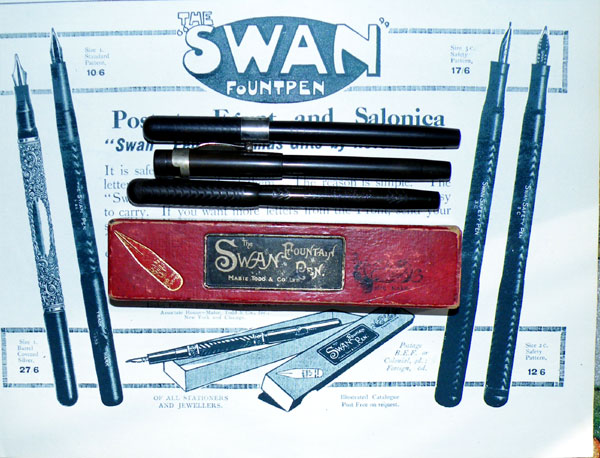

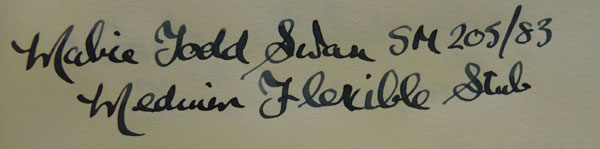

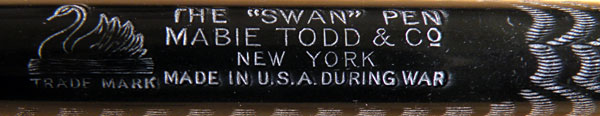

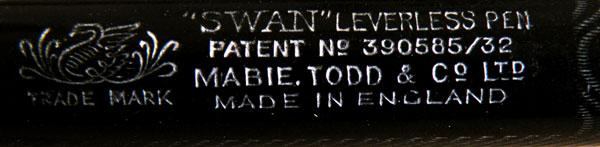

I’m sure some among you can put me right if I’m wrong, but I believe the term “fountpen” was only used by Mabie Todd, though on both sides of the Atlantic. I don’t think it means anything in the sense of specifying a particular sort of pen; it’s just a catchy term that stuck around for a while then faded away.

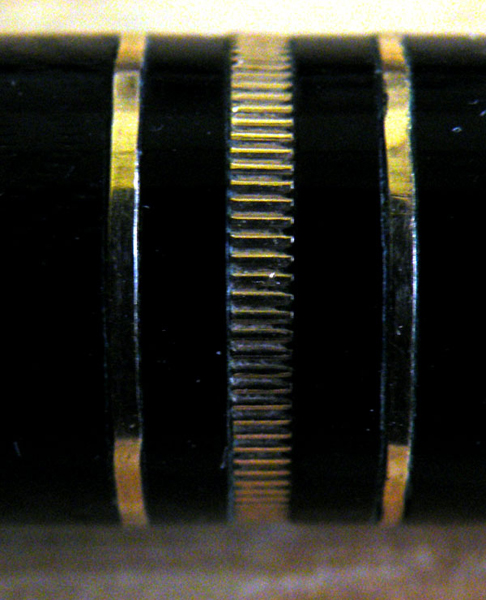

I’ve yet to own a Swan Fountpen, but I have had a Blackbird one. The Blackbird Fountpen eyedropper filler appeared in 1921 and had no more than a superficial resemblance to its older Swan sibling. Gone is the over-and under feed, replaced by the spoon feed that Mabie Todd experimented with for a while before settling for their ladder feed. The high dome of the Swan has become a very shallow one, almost a flat-top.

Very slender, the pen is long at 17cm posted, but so light that it balances well in the hand. These pens are not especially common. Perhaps they were a carefully inexpensive pen, keeping the cost down by sticking with the now outmoded eyedropper, when self-fillers were the coming thing. I imagine they were overtaken in sales terms quite quickly and were quietly removed from the market.