I have made some effort to ensure that this doesn’t become a purely Mabie Todd blog. Obviously, my own preferences show. Having looked at the statistics today, there are twice as many Mabie Todd posts as there are for Conway Stewart, the next largest, with Parker trailing sadly behind.

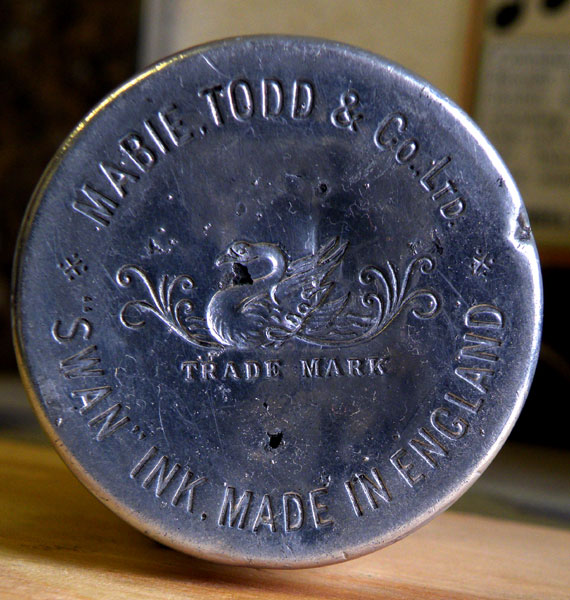

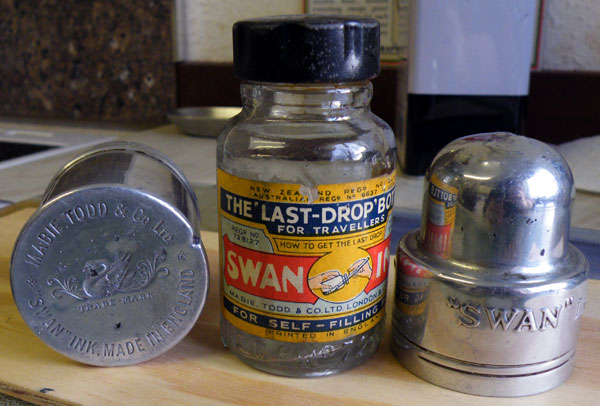

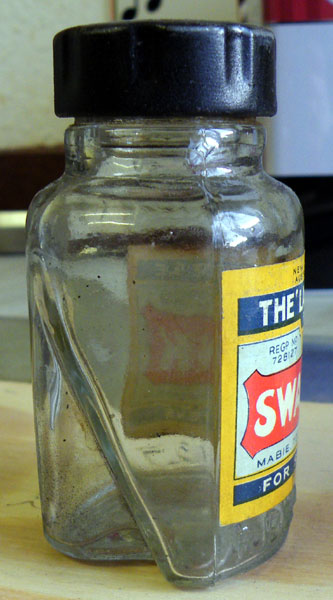

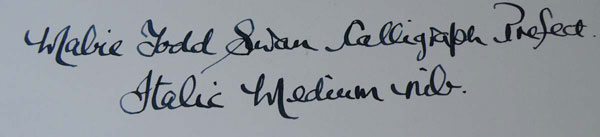

I enjoy all pens (except possibly Queensway, Scripto and the worst of the Platignums) but Mabie Todd pens, and Swans especially, stand out above everything else for me. There are no unpleasant surprises to sneak up on you when you work on a Swan – no glued sections or left-hand threads, no brittle barrels awaiting their chance to break. Everything comes apart as it should and reassembles without difficulty. Swan’s only peer in this regard is the pre-1950 Parker. Then there are the nibs: such is their elegance and grace of line that you can spot a Swan nib across the room. And they write so well whether they be the rigid Eternal, flexible, stub or oblique. I could continue this encomium of Swan (and those lesser fowls the Blackbird and the Jackdaw) indefinitely but I suspect you’ve had enough of the purple prose by now and you get the message anyway: I’m passing fond of Mabie Todd pens.

So I will continue to try to show some balance by the inclusion of the other estimable brands (of which there are many) but in the meantime here’s another Swan.

This is a Swan 3250 and the brass barrel threads indicate that it was an early example of the Swan post-war range. It’s not an outstanding pen except possibly in its condition, which is very good. A very deep red, it comes across as black in the photos. Not especially long at 13cm capped, it’s nonetheless a substantial pen.

This one’s good enough to be collectible and it’s an enjoyable writer too, a very precise medium with some flexibility and a snappy return. In its quiet way, it’s the perfect pen.

Oh, and a quick P.S. to whoever was searching for the info: The Conway Stewart 12 is 13 cm which is quite a standard length for a fountain pen. It’s somewhat slender. The 12 has a stunning range of colours. If you’re buying, check for cracks around the lever opening, which can be a failing in this pen.