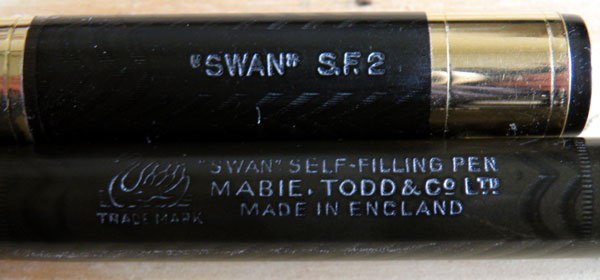

Here are two Mabie Todd lever-fillers in black chased hard rubber, one a Blackbird, the other a Jackdaw. Neither was assigned a model number and they’re the same length and thickness to the millimetre. The Blackbird’s cap tapers a little more than the Jackdaw’s and there’s less chasing on the Jackdaw. The Jackdaw has an unusually short lever. They’re both from the period around 1914-25, and are clipless, as was often the case in those days. We tend to think of the clip as an essential part of the pen but it wasn’t always seen that way. In advertisements as late as 1928, Conway Stewart made much of the fact that their washer-clips were easily removed!

I usually think of Blackbirds and Jackdaws as economy versions of the more expensive Swans. The trim is rather more likely to be chrome than gold, and on later Jackdaws even the chrome plating is quite thin. The nibs have shorter shanks, saving on gold, and they’re generally thinner than Swan nibs too. In technical terms, though, they’re pretty much the same pen, though not in this case.

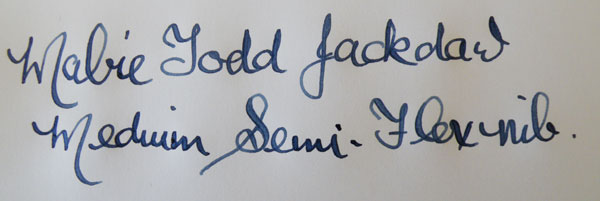

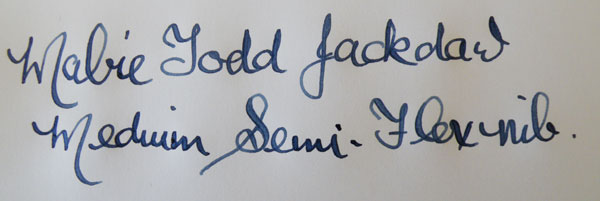

Swans, and all the other Jackdaws and Blackbirds I’ve seen, have ladder feeds. These two pens don’t. In both cases, the visible face of the feed is smoothly curved. They’re not spoon feeds, like a Waterman, either. They simply have feed channels, and, as such, are decidedly primitive feeds. They’re not replacements, as they’re marked “Blackbird” and “Jackdaw”. I re-sacced and tested the Jackdaw, and the ink supply kept up with a generous semi-flex medium nib very well.

Though these pens arrived in my repair queue around the same time, they came from different sources. I haven’t seen a Jackdaw of quite this type before – the short lever is highly unusual and very attractive – but the Blackbird is of a common type, essentially the same as the BB2-60. All the other examples I’ve restored had ladder feeds.

Pens like these are at the lower end of Mabie Todd production, aimed at clerks and school students, but they have their points of interest and they’re excellent writing instruments, every bit as good as the most expensive models. They had to be, of course. Fountain pens were the primary writing instrument, and those who could afford to pay least were often those who had to write most.

Neither of these pens shows much wear. The Blackbird still has its original sticker. It’s hard to read now, but it looks like the pen cost seven shillings and three pence new. The Jackdaw’s nib has been replaced with a Blackbird one at some time.

Now that I’ve found Mabie Todd pens with non-ladder feeds, I’ll probably be finding them all the time. That’s how these things go…