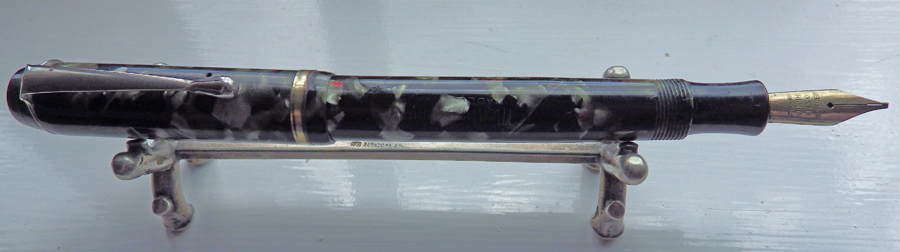

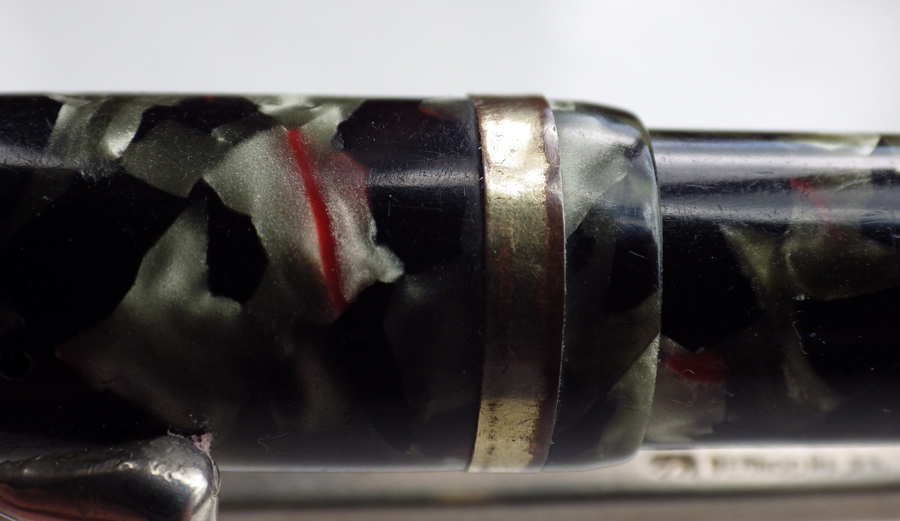

I’m writing this with a Ranga pen which I bought from Peyton Street Pens some time ago. It’s a big pen at 15 cm capped and 18.6 cm posted and it’s one of the few that I don’t post. Barrel and cap are hard rubber, the barrel black and the cap in that delightful wave pattern that Waterman called ripple. Though it’s big it’s very light due to the material.

India seems to be the only place that routinely works in hard rubber. I’m grateful that they do because it’s a material that I really appreciate.

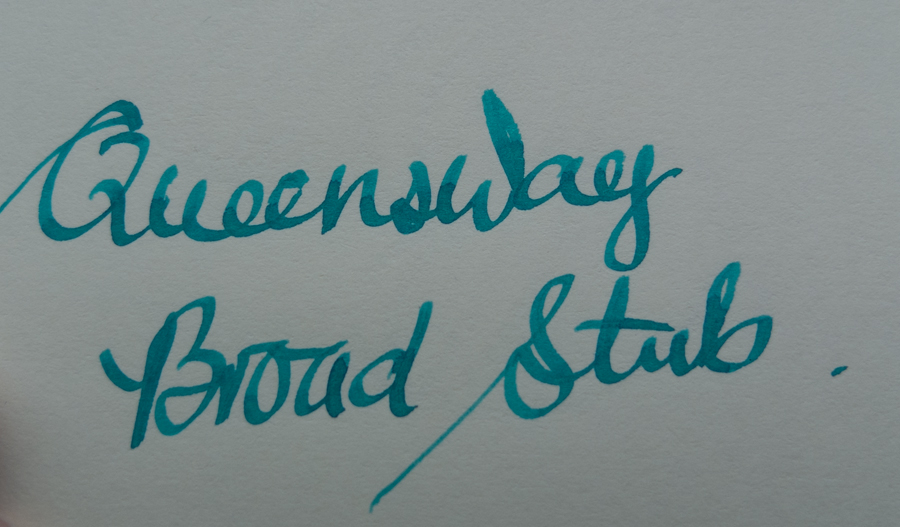

The other outstanding aspect about this pen is the nib. It’s a 60s – 70s Sheaffer Imperial nib, excess components from the time which are being very creatively used now. I love Sheaffer inlaid nibs and I love hard rubber, so this is a dream pen in many ways.

There are a couple of slight drawbacks. I couldn’t get a fine nib at the time I bought this pen so I had to settle for a medium. I suppose I could grind to a fine but it’s so smooth and reliable that I think I’ll leave it as it is. The other thing is the fitting of the cap which is a little imprecise. I sometimes have to try a couple of times but once I catch the thread it closes firmly. There is never any skipping or hard starting with this pen and it isn’t excessively wet either. Just right.

Looking at the Peyton Street Pens website I don’t think you can get this flat-topped version now. The latest pens using the Sheaffer nib, the Ranga Ebonite 4CS, is round topped, also a very attractive pen in a variety of patterns. I think there are more nib size choices too.

I would heartily recommend this pen to you all but there is one word of caution. Customs and Excise apply tax to anything from America these days and Royal Mail add on an £8 handling charge. This makes the pen a lot more expensive than it should be. I don’t understand how this charge works. I’ve had many pens delivered from Japan and China and they never seem to attract the attention of Customs. At one time I used to bid on pens in eBay USA and for years it was a good way of adding variety to my stock. Then, some years ago, customs began applying charges and put an end to buying American pens. Such a pity.