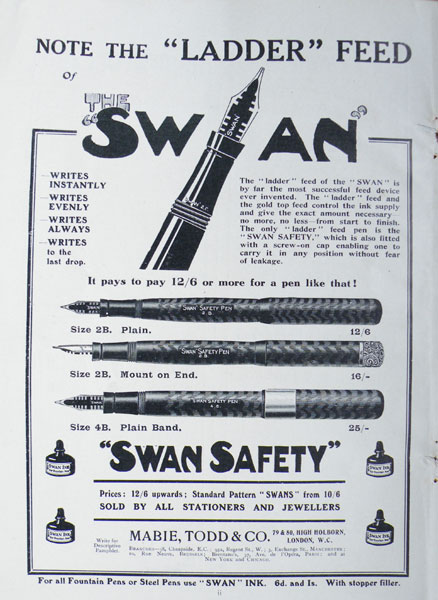

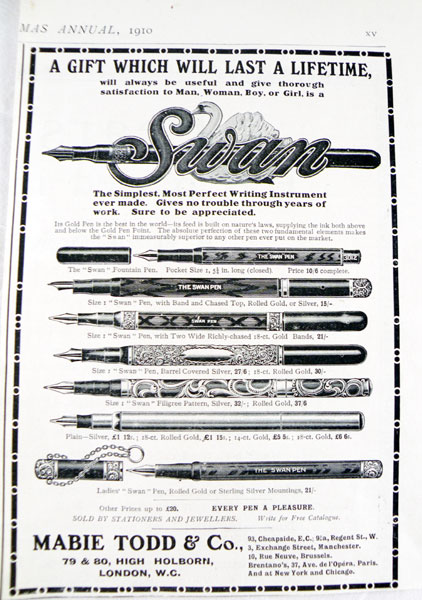

Advertisements are wonderful things. This one nails the introduction of the ladder feed for Swan pens at 1912. I have a suspicion that Mabie Todd continued to experiment with other feeds in Blackbirds for a time, but this was the date that Swans adopted the ladder feed which they retained right to the end.

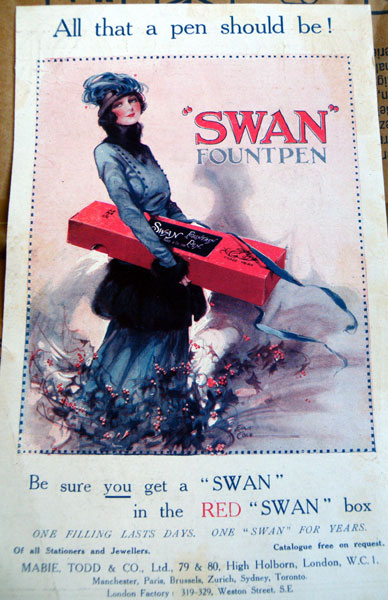

It was only the year before, 1911, that Swan had brought out the Safety Screw Cap so it’s new enough to also be made a feature in this full page spread. Would you pay 12/6d (62 ½ pence) for a pen like that? I would, and indeed I’ve paid a great deal more on many occasions. Safety Screw Caps are wonderful pens, fully modern in every respect except the filling system – and who can say the eyedropper filler is outdated, with so many on the market today?

On the middle pen illustrated, you’ll see what Swan call the top-feed. Discussion still goes on around this short-lived feature which Swan and a few other manufacturers installed on their pens in those years. It isn’t a feed, exactly, because it doesn’t extend far enough through the section to reach the reservoir of ink in the barrel. Only the ladder feed does that. However, it may redirect some of the flow of ink once it reaches the nib. Another possibility is that it shields the gap between the tines from the air and delays drying out. It’s quite likely that the gold top-feed did these things, to some degree at least, but it was entirely unnecessary. Later models dispensed with it and performed just as well. The ladder feed itself delivered the ink to the nib beautifully without assistance.

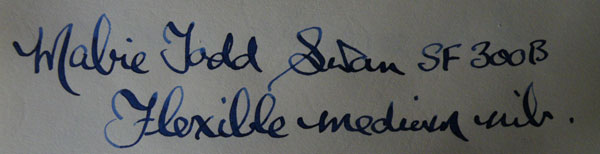

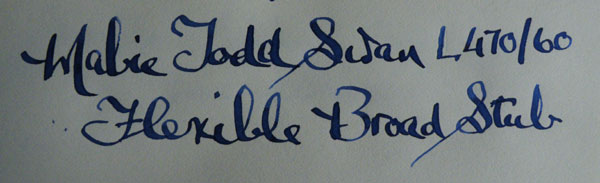

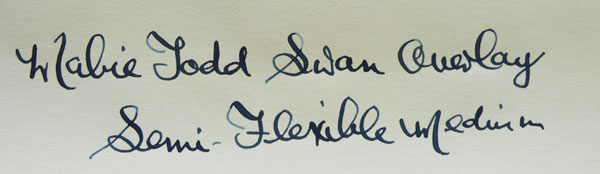

Provided the appropriate feed was matched to the nib, Swan’s ladder feed was (and remains, of course) superior to the other types of feed around at the time and it continued to hold that lead for many years. Properly adjusted, broad, stub and even flexible Swan nibs don’t suffer from ink starvation as so many of their contemporaries do. Even into the forties and fifties when Sheaffer and Waterman developed deeply-cut multi-finned feeds to control ink flow, Swan stuck with their tried and tested ladder feed which remained the equal of of these innovations.