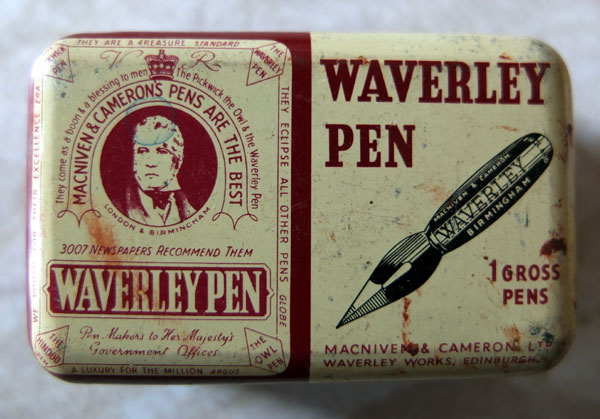

Once upon a time, children, in the long, long ago, there was an inspired inventor called Duncan Cameron. In those days of horseless carriages and ridiculous hats, people wrote with either a goose feather or a pointy steel dip nib. The feather was OK but the nib had a tendency to dig into the paper, sending a spray of ink, together with the occasional blot across your penmanship. Duncan addressed this problem by creating the Waverley nib, characterised by a narrow waist and and an upturned nib. Some say the nib was patented in 1850 and others say it was 1864. Either way, ’twas ages ago and I don’t have the energy to hunt down the truth of the matter (bad, bad historian; slaphand). Anyways, it was an immense success and the nib was taken up by almost everyone except schools where they liked to continue to torture the children with paper-slasher nibs.

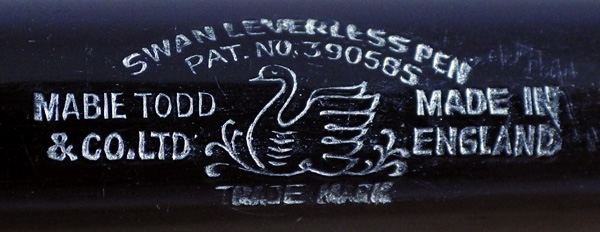

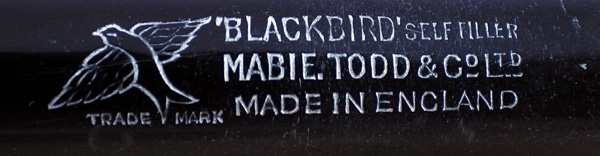

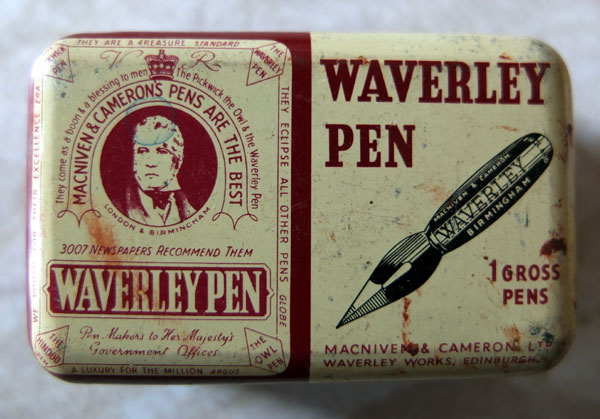

The Waverley nib became Macniven & Cameron’s best-selling product, and when they later decided to branch out into fountain pens like this splendid example:

they retained their well-known narrow-waisted, leaf-shaped nib as a selling point. What they didn’t do, of course, was tilt the tip of the fountain nib, for the simple reason that fountain pen nibs have smooth, long-lasting tipping material and have no tendency to dig into the paper. Such a thing would be redundant, so they didn’t do it. Here’s the fountain pen version of the Waverley nib, as straight and untilted as any other:

Probably independently, Sheaffer took up the idea of tilting the tips of nibs, particularly their tubular nibs, in the belief that this made them smoother writers. They were wrong, of course. Those tip-tilted Sheaffers don’t write any more smoothly – or indeed any different – than any competently-made nib.

Mr. Richard Binder took up the idea of the Waverley nib some time back, though for some reason he transferred the idea to fountain pen nibs, rather than dip nibs where it actually has some benefit. Now, I see in FPN, he has acquired the commercial rights to the term and is getting a little snappy about others using it.

Considering how much the term has been bandied about in the last few years, it seems unlikely that it could be legally limited in this way. It’s amusing, though, how these things come around.

They come as a Boon and a Blessing to men

The Pickwick, the Owl and the Waverley Pen

When Duncan Cameron named his improved nib after Sir Walter Scott’s novels and the area of Edinburgh where the main railway station is, he couldn’t have foreseen that the concept would give rise to litigious grumblings on the other side of the Atlantic a century and a half later. However, as we know, the history of the fountain pen is one of homages and copies. Truly, there’s nothing new under the sun!