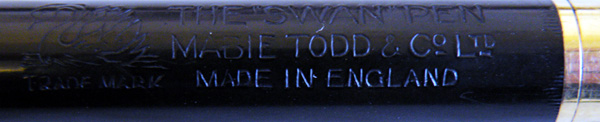

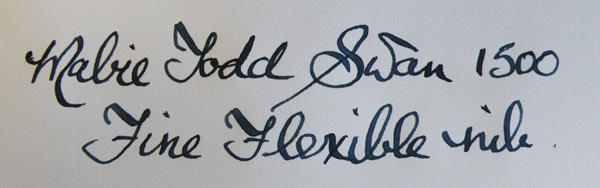

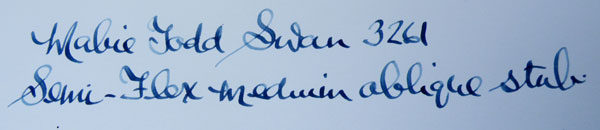

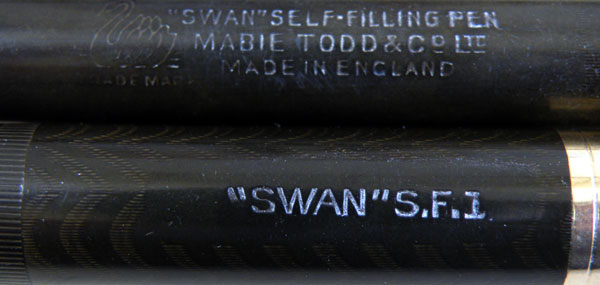

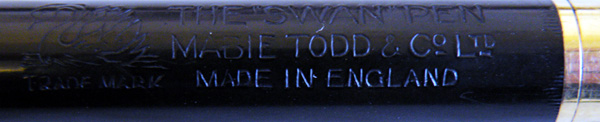

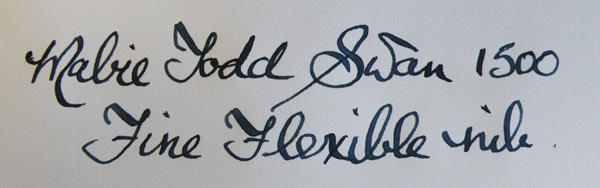

By the time the 1500 came along – probably around 1910 – Mabie Todd had been making fountain pens for quite a while. There seems to be real confidence and assurance with this model. No longer was the company trying to get a pen to work reliably and well. That has been done, and now it could concentrate on meeting the various needs of users, so the pen was presented with all the possible nib options – fine, medium and broad, oblique and stub, flexible, semi-flexible and, less usually, firm. Though the rest of the pen was British made (with the exception of a period during World War I, when production switched to America) the nibs were still made in New York.

1500s are perhaps the most commonly seen eyedropper pen now, and that gives an idea of how successful this model was and how well it was made. It remained in production for at least a decade, and survived competition with more technically advanced pens at the end of that period. Quite simply, its reputation was so high that people saw no reason to change. It remains a perfectly practical pen to this day and because of the superb quality of the nibs it is an especial pleasure to use.

By this time, other manufacturers had begun to drop the over-and-under feed. Though it successfully delivered ink from the barrel to the tip of the nib, it didn’t regulate it well. Too much or too little ink might arrive on the paper, and blobbing was a problem. The 1500 doesn’t suffer from these deficiencies. Perhaps the inclusion of the twisted silver wire at the back of the feed helps to regulate flow, but a well-set-up 1500 writes as well as any pen fitted with a spoon or ladder feed.

Like most pens made at that time, the 1500 is a slender pen. Most of its original purchasers would have been used to dip pens, so this would not have been seen as a disadvantage. The lack of a clip, however, was a nuisance, and Swan addressed this lack with the Swan Metal Pocket and a range of after-market clips. Though the slip cap fits securely, I suspect that clipping the pen to a pocket was never a very comfortable solution and there must have been accidents. It was only with the introduction of the Safety Screw Cap this issue was finally dealt with.

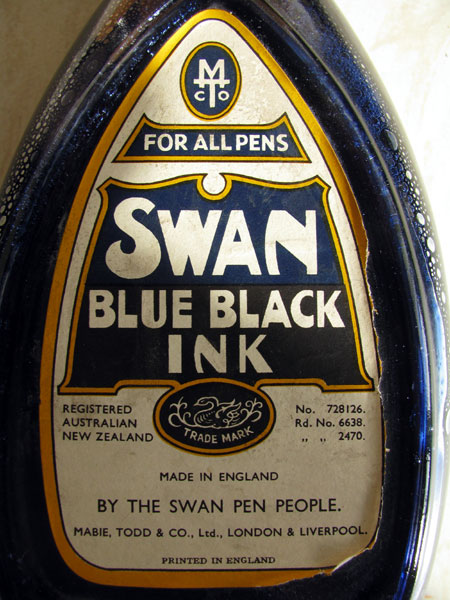

The 1500 comes in several guises. The most common version is the simple black chased hard rubber model, but more expensive 1500s had gold-filled barrel bands or even full overlays. This is the pen that helped to establish Mabie Todd’s early British market dominance, and it is said that fountain pens were referred to as Swans, in the same way as all vacuum cleaners were known as Hoovers.

For me, a flexible 1500 is one of my daily users. It requires no noticeable pressure to invoke a broad down-stroke, and transports me back to the days when light upstrokes and heavy descenders were just how people wrote, rather than a calligraphic technique.

At first glance it seems like an unnecessarily clunky solution but actually it’s eminently practical. Though well made it is light. The clip will attach firmly to any thickness of material from cotton shirt to tweed jacket and the pen is held securely but lightly, with no risk of marking it.

At first glance it seems like an unnecessarily clunky solution but actually it’s eminently practical. Though well made it is light. The clip will attach firmly to any thickness of material from cotton shirt to tweed jacket and the pen is held securely but lightly, with no risk of marking it. The clip is stamped with a beautiful Swan emblem; as this part would be visible, Mabie Todd wasn’t going to miss the opportunity to advertise their products.

The clip is stamped with a beautiful Swan emblem; as this part would be visible, Mabie Todd wasn’t going to miss the opportunity to advertise their products.