In the hierarchy of Mabie Todd pens the Jackdaw was the lowest in Britain, occupying the same place as the Swallow in America. These were school pens and were made to a lower level of quality than the Blackbirds and Swans. It’s rare, for instance, to find a Jackdaw that doesn’t have noticeably worn plating. The nibs, though equally as good to write with as those fitted to the more expensive pens, were shorter in the tail and a little thinner.

For some Jackdaws that position is now reversed. Collectors vie for ownership of the colourful Jackdaws made in the mid to late thirties which shared the bright patterns of the Visofils. This glorious red and black Jackdaw is an example of these especially beautiful pens. In shape it closely resembles the brightly self-coloured Blackbirds of the same period.

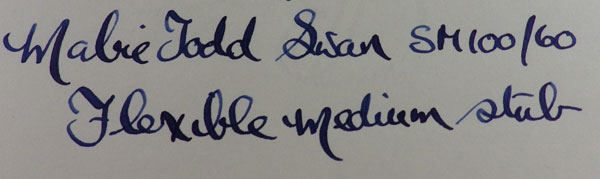

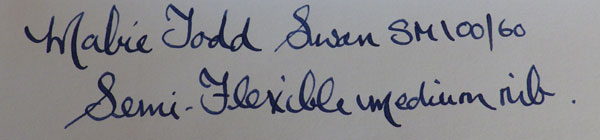

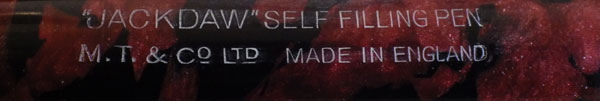

A collector of “bird” pens – Swans, Blackbirds, Pelikans, Eagle pens and the like – asked me once if the Jackdaw and Swallow had bird barrel imprints like the Swan and the Blackbird. I had neither to hand at the time and couldn’t answer with any degree of certainty but here it is:

No bird imprint on the barrel but a splendid Jackdaw Trade Mark on the box and the paperwork. I still can’t say about the Swallow, having only handled a couple and that a long time ago.

School pens get a harder time than any other. The result is that these colourful Jackdaws are not at all common, more’s the pity. Like the Visofils, they’re not often seen now. That makes such a fine example as this all the more to be valued.